Non-technical Research Statement

My research interests are in algebraic topology, specifically in homotopy theory.

Broadly speaking, topology is a generalization of the study of shapes. These shapes can be abstract and hard to visualize, so we study them though algebra. In particular, in homotopy theory, we use algebraic tools called invariants to describe whether two shapes are the same or different.

Homotopy theory has its origins in algebraic topology, but its core tools and ideas have spread and found use in other areas of mathematics. In my research, I apply the computational methods of homotopy theory to answer questions about the modular representation theory of finite groups.

Below is a brief, undergraduate-level introduction to the kinds of things I think about. For further details on my research, check out my Research page.

Algebraic Topology

Broadly speaking, topology is the study of objects called topological spaces, which generalizes the study of curves and surfaces in $\mathbb{R}^3$. Though we can visualize and geometrically think about curves and surfaces using the tools of multivariable calculus, the generalizations of these shapes are difficult to visualize in higher dimensions. Moreover, we are interested in studying properties of shapes that are independent of how they exist in $\mathbb{R}^n$. For example, rotating or scaling don’t change the fundamental properties of these shapes, and more generally, we might consider two shapes to be the same if we can continuously deform from one shape to another.

To think about these abstract spaces, we can use algebraic tools called invariants to determine whether two spaces are the same or different. For example, recall that a topological space is simply-connected if it “has no holes” (e.g. $\mathbb{R}^2$ is simply connected, but $\mathbb{R}^2-{(0,0)}$ is not simply connected). This invariant shows up in multivariable calculus in the following classical theorem about identifying conservative vector fields.

Let $\overrightarrow{F}$ be a vector field on a simply-connected domain $D \subset \mathbb{R}^3$. If $\text{curl}(\overrightarrow{F}) = \overrightarrow{0}$, then $\overrightarrow{F}$ is conservative.

In other words, this theorem tells us that we can perform a calculation (e.g. integrating an appropriate vector field) to determine if a topological space is not simply-connected. This illustrates the key idea of algebraic topology: in order to understand an abstract topological space, we would like to calculate algebraic invariants, such as fundamental groups, higher homotopy groups, and/or (co-)homology groups. Moreover, these invariants are typically functorial - that is, maps between topological spaces should give maps between their algebraic invariants. In this way, many topological questions can be turned into computations using linear algebra.

Homotopy Theory

The key question of algebraic topology, or more generally, homotopy theory, is the following idea:

Given a collection of objects and some notion of equivalence, we would like to determine whether or not two objects are the same or different.

For example, in topology, the objects we study are topological spaces, and one notion of equivalence is homotopy equivalence. Examples of topological spaces include circles, spheres, and donuts, and anything you can form out of rubber. We say two topological spaces are homotopy equivalent if you can stretch, shrink, or deform one into the other through continuous maps. This means that you are not allowed to cut, pierce, or attach things to the object you start with.

In the eyes of homotopy theorists, it is useful and convenient to replace equality with the notion of homotopy equivalence instead. Making this replacement means we are now considering the homotopy category. This leads to the usual joke that algebraic topologists cannot tell coffee mugs apart from donuts, since this notion of equivalence is too coarse to tell the two apart.

However, we can distinguish topological spaces up to homotopy by identifying certain traits (called invariants) such as homotopy groups and (co)homology groups. We have various powerful tools at our disposal to compute these invariants.

Stable Homotopy Theory

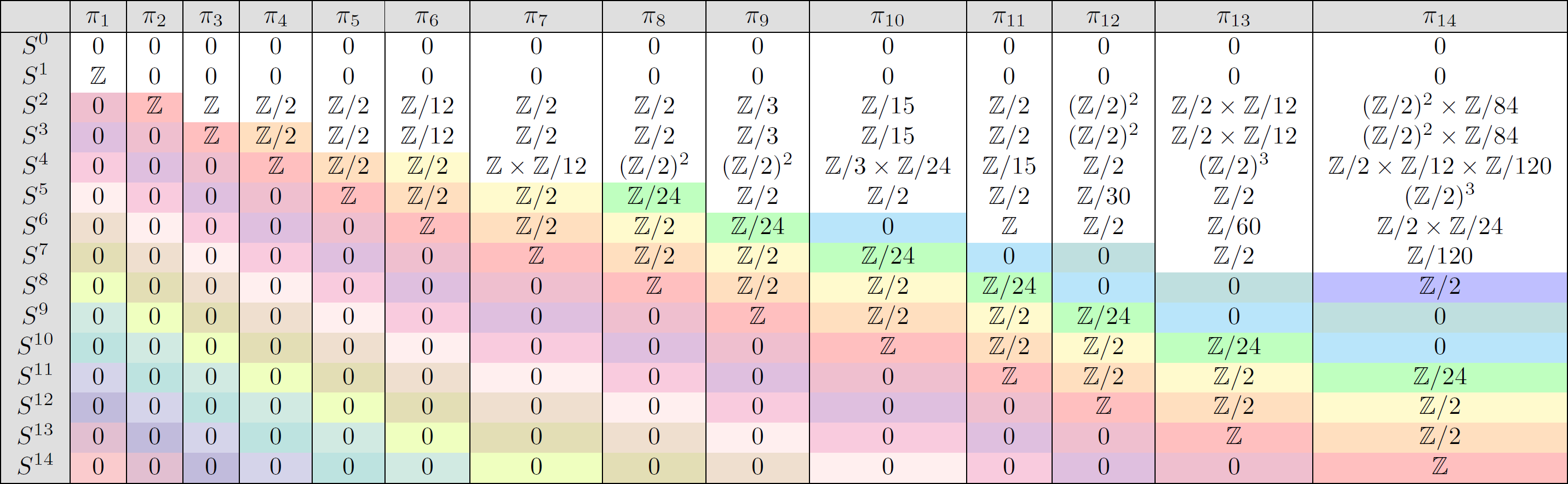

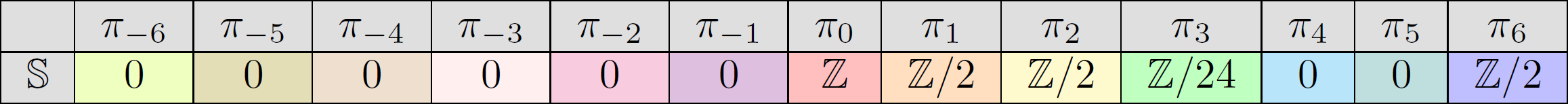

We enter the world of stable homotopy theory when we begin to investigate the structure of the homotopy category. For example, if we consider the most fundamental topological spaces, the $n$-dimensional spheres, we notice some interesting patterns in a table of their homotopy groups:

This is no coincidence: this stabilization of homotopy groups is the content of the Freudenthal suspension theorem. One can form a similar table for any other other topological space (Exercise: If we replace $S^0$ with a space $X$ in the first row, what should we replace in the following rows?). This leads one to look for new objects that can capture this stable information. In other words, we would like to collapse our tables along the anti-diagonal (roughly). The objects that capture this information are called spectra, and studying the homotopy theory of spectra is known as stable homotopy theory.

Axiomatic Stable Homotopy Theory

It turns out that we can generalize this story to other settings, which brings us to axiomatic stable homotopy theory. We can formalize the story above with categorical axioms, and many of the important theorems and tools of algebraic topology become formal consequences. These axiomatic structures are called stable model categories (or stable infinity categories, depending on your formalism). Some instances of these structures occur in modular representation theory, derived categories of modules over rings, the derived category of quasi-coherent sheaves over nice schemes, etc.

One can then try to prove theorems in these other settings by mimicking or taking inspiration from classical theorems in algebraic topology. On the other hand, one can also try to understand open questions in algebraic topology by understanding the analogous questions in other axiomatic stable frameworks.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning about algebraic topology and homotopy theory, I recommend the following resources:

- For a quick undergrad-level introduction to the ideas of homotopy theory, see this slide talk that I gave for the UT Austin Math Club.

- The standard introductory textbooks for algebraic topology are Allen Hatcher’s “Algebraic Topology” and Peter May’s “A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology”.

- For a quick introduction to stable homotopy theory, see Neil Strickland’s survey “An Introduction to the Category of Spectra”.

- There’s a lot of scattered references regarding spectra, as the historical development of spectra was complicated. It turns out that there is no category of spectra that has all the properties that one might want, and there are various flavors of spectra with different properties.

- The standard references are Elmendorf-Kriz-Mandell-May’s “Rings, Modules, and Algebras in Stable Homotopy Theory” (#83) and Mandell-May-Schwede-Shipley’s “Model Categories of Diagram Spectra” (#96).

- For a quick survey of axiomatic homotopy theory (model categories), I like W. Dwyer and J. Spalinskies’ “Homotopy Theories and Model Categories”.

- A perhaps more modern approach is to use the language of infinity categories. Jacob Lurie wrote a column in the Notices of the AMS, “What is an ∞-category?”.

- For a quick survey of axiomatic stable homotopy theory, check out this survey by Neil Strickland.

- You can also ask that these spectra behave like rings (“Brave New Algebra”), and see what theorems from abstract algebra still hold.

- For example, see this survey on “Commutative ring spectra” by Birgit Richter.

- Similarly, one can do Galois theory: see this monograph on Galois extensions of structured ring spectra by John Rognes.